The following is adapted from The Life We Now Live, a 15-lesson study on grace in Galatians, written by CJ Harris .

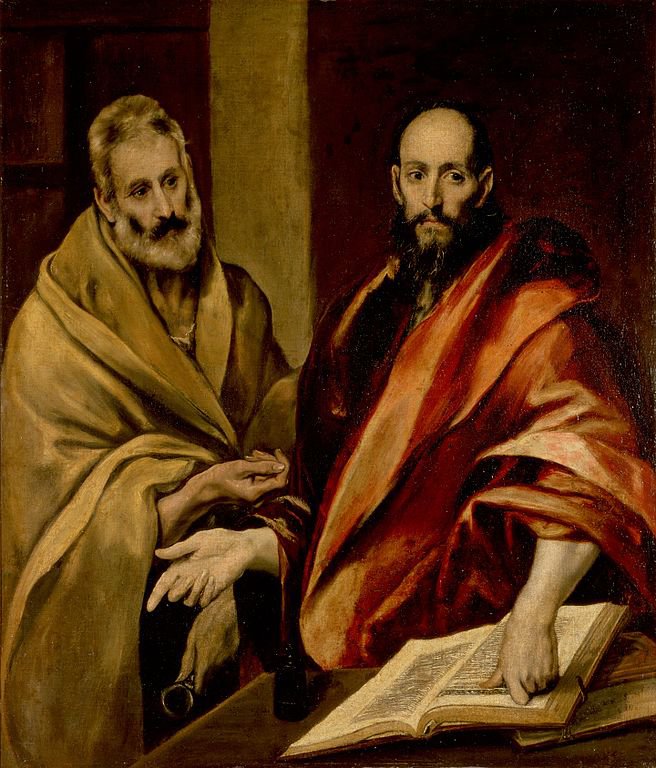

A lot of people don’t like Galatians 2:11–14. This passage has confused, excited, and infuriated scholars since the early years of the church. Christians often think of the apostles as nearly-perfect, saintly figures who spoke and taught in perfect unity, yet here and in Acts we find disagreements—even between people the Holy Spirit used to write Scripture.

A Few Wrong Interpretations

This passage has fueled debate and speculation among those who try to promote a false gospel. Roman Catholics, who believe that Peter was the first pope and therefore could not commit doctrinal errors, try to present this dispute as a trick—a sort of play that Paul and Peter acted out to demonstrate the value of unity to the early church. But if true, this would be the only example of trickery as a teaching method in the Bible. And we can find no evidence in Scripture that this dispute was anything but an honest disagreement.

Many liberal theologians, however, like to present this disagreement as a huge conflict between two branches of the early church. These scholars weave an unsupported narrative of church history, claiming that the Paul-branch and the Peter-branch of the church fought each other until the Paul-branch of the church finally won out in the second century—from which we have our earliest copy of Galatians in the Greek manuscript Papyrus 46. Around that time, supposedly, members of the Paul-branch re-wrote Paul’s epistle to the Galatians and included this passage to show the value of unity. They apparently thought that including an example of early conflict and resolution would smooth over any remaining disagreement.

Despite the lack of scriptural or historical basis for these views, many groups have used this passage to that the Bible has always included human error and contradiction.

But today we can look at this passage as the early church did—not with a deconstructionist agenda, but as Christians struggling to understand the importance of the gospel to everyday life.

The Confrontation Between Paul and Peter (vv. 11–14)

If any person in history could have claimed importance or authority greater than the gospel, it would have been Peter. He was one of Christ’s closest followers and the de facto leader of the early believers. Jesus said He would build His church on the testimony Peter made, and it was Peter who preached at Pentecost when the Holy Spirit first appeared to believers.

But Paul shows in this passage that even Peter, the supposed super-saint, could distort the gospel by mistake. Here Peter had fellowshipped with a group of Gentile Christians in Antioch, eating and talking with them. But when some Jewish Christians arrived, Peter reverted to Jewish tradition, refusing to eat with the Gentiles and acting aloof. Worse yet, Peter’s example led the other Jews to act hypocritically, as well. Peter had forgotten the same unity he had preached in Jerusalem.

This public sin required a public correction, so Paul confronted Peter in front of all the others, pointing out his hypocrisy and the disunity it created. Even Peter could not reject the unity created by the gospel.

Church History Side-Note

This situation brings to mind the Donatist controversy in the fourth century. During the reign of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, Christians faced horrific persecution—perhaps the worst in Roman history. Near the end of Diocletian’s reign, however, he allowed Christians a way to save themselves from imprisonment or execution. If they renounced Christ and made an offering to the emperor, thereby re-entering the official religion of Rome, they would receive their freedom.

Many Christians refused, and therefore lost their lives. But some did recant Christ and return to society, distraught and broken. Unfortunately, when the church most needed unity in Christ, a group of believers had fallen and removed themselves from the body.

But after the Emperor Constantine came to power, he professed Christianity and ended all official persecution of Christians. The church grew, as previously secret Christians could now share their faith publicly. Even some of the Christians that had recanted during Diocletian’s reign came back to the church.

But some Christians couldn’t accept their brothers and sisters back into the fold. A group of North African bishops called the Donatists taught that if a believer ever recanted Christ, they could never be allowed back into a church, nor could they take part in any ordinances, such as communion. Furthermore, any Christian who had been baptized by a preacher that had later recanted must be re-baptized.

This teaching reflected many doctrinal errors, but perhaps the most serious was the elevation of the gospel messenger over the gospel. A person does not accept Christ and share that acceptance through baptism by the power of his preacher. He does not lose his salvation because his preacher, or gospel messenger, commits a heinous sin. The gospel’s power does not depend on its messengers.

Thankfully, a group of church leaders convened to discuss the re-admission of recanting believers back into the fold. They condemned the Donatists for rejecting the grace of God to forgive and redeem His children.

It’s easier to see where the Donatists rejected the power of the gospel, but looking back at Galatians, where did Peter go wrong?

Problem #1: Peter Separated from Fellow Believers Because of Fear (vv. 11–12)

We sin by motive before we sin by action. Peter feared the disapproval of other people, and until the arrival of the strict Jewish believers, he had no problem fellowshipping with the Gentile believers. But as soon as these others arrived, he broke unity. He wanted the approval of those that revered Jewish tradition over Christian unity.

We should never attack the fellowship of the Spirit. Sure—we needn’t cooperate with every venture by every church, but we should not attack the genuine efforts of others who truly preach Christ. We can offer reasons from the Scripture why we disagree with their methods or philosophy, and we can certainly sharpen each other through fellowship in the Word, but we must maintain unity in the same love Christ showed us.

Problem #2: Peter’s Example Led Others to Break Unity (v. 13)

Paul’s example led other believers to reject the unity they had in Christ. They assumed that if Peter broke fellowship, it was OK for them to do the same. Even Barnabas, the Son of Encouragement and Paul’s good friend, fell into the same trap.

Peter’s hypocrisy lacked grace, unity, and love—and it spread quickly.

Problem #3: Peter Misrepresented the Gospel (v. 14)

In Ephesians 2:7 we learn that Christ saved us in order to show us the immeasurable riches of God’s grace. And He uses us to share that grace with others here on Earth.

So when we create unnecessary division and strife, placing chasms where Christ built bridges, we commit a grievous sin against God and the work He accomplished through Jesus. If Christ came and suffered and died to bind us together in God’s grace, how dare we corrupt His gospel by trying to rip those bonds apart?

Ultimately, Peter was wrong because he painted a false picture of the gospel. Of course he didn’t do so on purpose, but he gave others the idea that the gospel was for some people, but not so much for others.

We can do the same thing when we let our culture get in the way of biblical unity. Rules and standards are helpful for a church body, but people who don’t conform to them should not receive any less love. It’s easier to hang out with other Christians who practice their faith the same way we do, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t show grace to those with whom we disagree.

Paul says in verse 14 that Peter’s actions were not consistent with the truth of the gospel. Peter believed that salvation was based on faith in Christ alone. But his actions added other requirements to Christian unity—like culture, practice, and ethnicity. And those requirements made it impossible for Peter to serve Gentile believers in love.

Again, this isn’t to say we shouldn’t have standards or rules of conduct in a church. We must have strong, biblical reasons for what we do (Rom. 14:22–23). Otherwise, we can find ways to justify almost any sinful practice.

But unbelievers should not look at us and find reason to criticize Christ. They should not see us tearing each other down over petty differences. Instead, they should see first what unifies us—the gospel of Christ.

Grace is available to all Christians, but do our actions reflect that belief?

The Life We Now Live is a study of God's grace in the Epistle to the Galatians. The above lesson is just a small piece of an exploration of our new relationship with a loving, holy Father, as well as our new liberty to love others as Christ loved us. For more information, including an overview and samples, see the product page linked below.

CJ Harris is the managing editor for Positive Action, where he helps plan, develop, and launch Bible curricula for churches and schools. Having served as a youth pastor and Sunday School teacher, he has a passion for teaching young people about the glories of their God. A bit of a history buff, CJ received his Ph.D. in Church History in 2011, based on a study of Reformation-era missions philosophy. He and his wife—also a student and teacher of history—have two sons.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons